Exploring the most complex time crystals yet with quantum-centric supercomputers

January 28, 2026A team of researchers created one of the largest and most complex demonstrations of a time crystal on an IBM Quantum Heron chip, as described in a paper published today (28 Jan) in Nature Communications. This work from a team including Basque Quantum (BasQ), NIST, and IBM scientists showcases the power of today’s quantum computers to drive meaningful work in other scientific disciplines—and the possibilities that open up when quantum and classical hardware work together as part of a quantum-centric supercomputing architecture.

What is a time crystal?

Crystals are matter organized into repeating patterns that resist deformation. We’re used to seeing crystals in nature: snowflakes, diamonds, and table salt all form distinctive shapes due to the patterns their molecules stubbornly form in space. Time crystals form their resilient patterns across time, rather than space.

However, our typical crystals assume these structures without the input or release of energy—they are in thermal equilibrium. Time crystals are different—rare examples of non-equilibrium dynamics. A time crystal is a phase of matter that only exists out of equilibrium.

Periodically pump energy into certain kinds of quantum systems and they will exhibit stable rhythms, such as the spins of particles flipping back and forth. The system locks into a cycle, flipping in a pattern that typically lines up with every other beat of the pump. This makes them rare counterexample to the expectation that quantum information gets scrambled. Even as more energy enters the system, a signature of the original quantum state remains.

How IBM hardware helped push time crystals to new scale and complexity

Time crystals are hard to set up and delicate, and have only been created a handful of times in laboratory settings. They require precise arrangements of particles in highly-coherent quantum systems that are well-shielded from heat and noise.

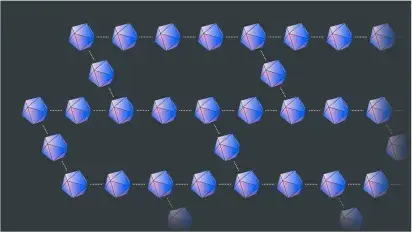

Until very recently, these constraints meant it was only possible to study one-dimensional time crystals in laboratory settings: Researchers would set up chains of atoms, each one linked to the next in a line. Researchers had theorized about time crystals at larger scales, but they are difficult to model computationally. Add more dimensions to a time crystal and the overlapping interactions quickly grow too complex to predict with classical methods.

IBM quantum computers, with their processors isolated from the heat and noise of the universe, are excellent sandboxes for studying quantum phenomena like time crystals. The team behind the most recent research announced that they constructed a 144-qubit, two-dimensional time crystal on the Heron chip. As qubits are quantum objects, the researchers aren’t merely simulating a time crystal, but creating one using qubits as the basic unit.

In two dimensions, signals move in much more complex ways through the many-body system. Dynamics emerged that had never previously been studied in tabletop experiments or classical simulations. “Dimensionality matters. It’s not the same to have things align in one dimension as in two. And size matters,” meaning that a larger time crystal will act in different ways from a smaller one, said Nicolás Lorente, a researcher at the Center for Materials Physics in Donostia and part of BasQ, who is an author of the paper.

Up until now it wasn’t clear if a time crystal of this complexity was possible outside very artificial models, said Niall Robertson, IBM research scientist and another author of the paper. But this work helps show that 2D time crystals are robust beyond very small scales, which could have implications for future research. And, at the largest crystal size they studied, the team tested parameters on Heron that they were unable to simulate on a classical computer.

“We absolutely needed the quantum system to be able to probe something as big as we did,” said Eric Switzer, a theoretical condensed matter physicist at the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) and an author of the paper.

This work sets the stage for exploring time crystals at new depth. Researchers are interested, for example, about the role of disorder in time crystals. Now, the researchers are testing just how much disorder they can get away with; some amount of disorder is necessary to stabilize a time crystal, but too much disorder threatens to shatter it.

Better understanding time crystals could shed light on a broad range of “Heisenberg-type interactions” in materials science where the spins of particles influence each other. There are implications for studying single-molecule magnets, metallic chains, and quantum dot-based architectures (a class of nanoscale semiconductors with many technological applications).

Quantum and classical compute, working together

Whenever there is an interesting quantum result, one important task is verifying it. The team used a state-of-the-art approach to simulate the quantum state on a tensor network using belief propagation, then compared the results to those from the quantum computer.

All quantum computations can be represented using very large tensors—mathematical objects with ordered data like spreadsheets, stacks of spreadsheets, or filing cabinets full of spreadsheet stacks. However, the tensors required to simulate quantum systems are too large to simulate using any classical compute resources.

Tensor network methods use classical compute to simplify these large tensors into a larger number of smaller tensors, though sacrificing some accuracy in the process. Each piece captures part of the system, and the connections between pieces capture how those parts relate. Tensor networks can be used to approximate quantum states on classical computers. Meanwhile, belief propagation is a sophisticated method to approximately update or extract information from a quantum state represented using these tensor networks.

Much of the current race for quantum advantage can be understood as a competition between quantum computers and the best tensor network methods. However, in the quantum-centric supercomputing paradigm, we can also use tensor method techniques to improve our quantum computations themselves. In this new era of quantum computing, we seek to find algorithms that incorporate quantum circuits and tensors simultaneously and split each of these tools among the hardware that can best tackle them

In this paper, researchers are beginning to explore how to use classical techniques to refine the quantum execution. They implemented new error mitigation methods to increase the accuracy and reduce the error bounds from the quantum results.

This is an example of where we expect the most exciting quantum computing work to go soon: quantum and classical HPC resources working together in quantum-centric supercomputing (QCSC) architectures. Many HPC executions will involve operations broken up between CPUs, and QPUs, and GPUs with each piece of hardware handling only the mathematics to which they are best suited.

The next big step, the researchers said, will involve trying to build a more complex time crystal in the more interconnected environment of IBM Quantum Nighthark chips, where qubits link to up to four neighbors, rather than two or three on Heron. More connectivity means more complexity, and the potential to capture new dynamics.

The team is also interested to see what GPUs can do for the classical side of the work, Robertson said. As QCSC advances, their work continues.